The French Revolution conjures up images of Marie Antoinette, angry mobs, and guillotines. But amid all the turmoil and upheaval, the precision of the modern metric system was born. The same revolution that swept away the French monarchy and the feudal system also eliminated the country’s outdated, inconsistent form of measurement previously. Eventually, it would transform measurement around the world. Like the revolution, the metric system — with its meters, liters, and grams — was an idea whose time had come.

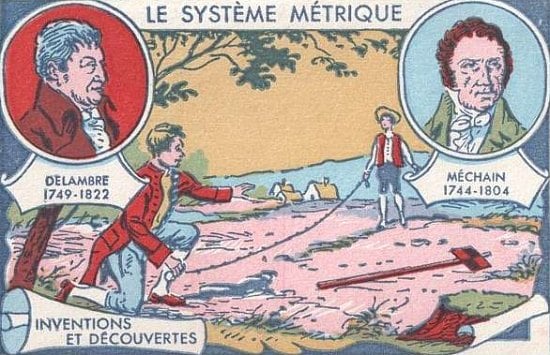

French surveyors Pierre-Francois-Andre Mechain and Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre were sent to measure Earth's arc between Dunkirk and Barcelona in an effort to create a universal distance measurement. Their measurements had some errors, but the definition of the meter took hold. Credit: NIST

For many French revolutionaries, the metric system served as an important symbol of change. By breaking away from the older system of measurement, they were also symbolically breaking free from the old regime of the monarchy and the nobility. The meter, kilogram, and liter became symbols of a rational, enlightened new country, where democracy had replaced inherited power.

How Did Measurement Work Before the Metric System?

The precursor to the metric system was chaotic, to put it mildly.

In France, and throughout Europe, it was common to use different measuring units based on the product being measured. For example, wine was measured using different units from milk. Measurement standards were different from village to village, or even from one merchant to the next. The tools used in the measurement process were rarely standardized, so it was hard to duplicate them. A “cup” measurement would refer to a specific cup; a “rod” length meant a specific rod.

Of course, these idiosyncrasies made buying and selling merchandise a challenge. Accusations of fraud and cheating were common, if difficult to prove.

The Metric System: Measurements Based on Nature

Instead of the old, unreliable measuring tools, the metric system introduced a system of measurement based on nature. This meant that anyone could replicate the measurements — it served, essentially, as a way to democratize measurement. The meter, for example, was defined as 1 ten-millionth of the distance between the pole and the equator. Units for measuring capacity and mass (the liter and the gram) were derived from the meter, so every unit in the metric system is ultimately based on the measurement of the earth.

The French Academy of Sciences was so devoted to the concept of impartial measurement that they sent a team of surveyors to carefully measure earth’s arc. The goal was to derive the length between the pole and the equator by analyzing the “arc” of the earth between Dunkirk and Barcelona. It’s worth noting that the surveyors, led by Pierre-Francois-Andre Mechain and Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre, made some errors in their measurements. Still, the meter that they came up with has survived, unchanged, to our own times.

The French National Assembly and Base-10 Calculations

During the peak of the French Revolution, in 1790, the National Assembly ordered the Academy of Sciences to create the new system of measurements. The assembly asked for a system that was reliable, straightforward, and consistent. In response, the academy developed a plan to make the metric system easy to use. Each unit was broken down into small sub-units by dividing into tens. This made calculations easy — no more multiplying by 12 (to convert inches into feet) or by 16 (to convert ounces into pounds).

Napoleon and Beyond

Napoleon Bonaparte was an outspoken critic of the metric system. He said that its proponents were “tormenting the people with trivia.” The emperor floated his own system of measurement, a modified metric system using the old names for new quantities.

However, the true metric system had already taken root, and it spread quickly. By the mid-19th century, it was firmly established in France and had spread to much of Europe. England resisted the system, but eventually even the British were forced to use the metric system for international commerce.

This early version of the kilogram from 1790s France. May have been pirate treasure for a time. Credit: NIST

International Recognition

In 1875, the meter was officially recognized as the international standard of measurement. In that year, global leaders signed the Treaty of the Meter. The United States, which was just becoming a world power, also signed the treaty. The treaty gave rise to the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, which was charged with overseeing standard measurements and issuing prototypes of the meter to all participating nations.

in countries like the United States, which resisted adopting the metric system, scientists and engineers used the system. Its standardized measurements and decimal units made it a natural fit for these disciplines.

In 1960, the General Conference on Weights and Measures formally revised and updated the metric system, establishing base units for time, electric current, thermodynamic temperature, and mole. The modern metric system is known as the International System of Units, or SI (for its initials in French).

The metric system has undergone a number of changes since it was first championed by French revolutionaries at the end of the 18th century, but its fundamental focus on standardized units remains exactly the same.